Editor's Note:

Chris Battis sent me a web site entitled "The Old Man and The C:\" by Tom Pry. Tom is a retired broadcast editorial writier and has a Blogger Site about "Life, Past and Present, if not necessarily the Future". I found his commentary to be tongue in cheek and his humor hilarious. He has a joke of the day and cartoons throughout his commentary.

|

|

Tom as he appears Today |

Tom As a Boy? |

Both Pictures are from Tom's Web Page

Turns out Tom also served in Broadcasting and Visual Activity (B&VA) Korea from 1957 to 59. He preceded my TDY to Korea by three years. I was at Korea Detachments in April-May 1962.

Tom is a very interesting guy and promised he would send some personal experiences about his tour. So far he has sent two articles that appear below. One is an account of an Army buddy, "Blackie" that appears on his page (May 2005 Archives). I wish someone would think as much of me someday to write as nice a tribute.

The other is both an interesting and sad account of Military Pay Certificates (MPC's) and the day all MPC's were changed in Korea resulting in the loss of "family fortunes" by many Koreans. I had never heard this story.

![]()

|

|

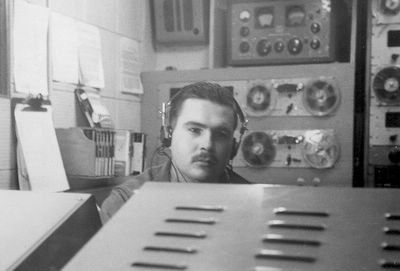

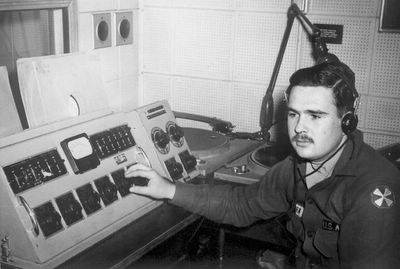

Britt A. "Blackie" Bowden |

Blackie in VUNC Master Control Room |

“Blackie” was not his real name, but that's what we called him in the Army, as a diminuitive of “Black Bart,” one of his favorite nicknames and role models. He was fairly short, not quite plumpish, with dark hair and dark eyes, combined with fair skin, and a heavy beard, plus a mustache.

Handsome? No. Irresistible? Pretty much.

Unforgettable? You bet your sweet ass!

Unlike when I originally ran this, I will tell you his real name: Britt A. Bowden. I mention it now because Blogspot belongs to Google, and that will end up in their unbelievable data banks where, maybe, someone else will be looking for him. It's important only for that reason: to us, he was Blackie.

It's been 42 years since I've had any contact with or communication from Blackie. With him up in the northwestern U.S. and me being .. well, just about every place BUT the northwest, our chances of running across each other were essentially nil. We were together in the Army from late 1957 until spring of 1959, all but two months of that in Korea . Then silence until early 1961, when I got a phone call, then a tape.

Then more silence, as each of us got on with the business of living our rapidly-diverging lives and raising our new families.

Periodically, I've run Blackie's real name through various internet search engines, with no results. Then, the other day, I got a hit: a golf tournament named after Blackie. I e-mailed the publicist for the sponsoring group, an advertising trade organization, telling her (Katie) of my connection with the namesake of the tournament; “There can't be that many Blackie's in this world. You're in the right city, so I guess what I'm asking is if Your Blackie is the same as My Blackie.”

A couple of notes exchanged before confirmation of the near-certainty that, indeed, they were one and the same person. Along with that confirmation came the bad news: Blackie had died of cancer in the early 80's. Katie said she thought he had one son, David, but she didn't know how to contact him.

Katie, a young academic, is of too tender an age to have ever met Blackie personally, but she's heard such stories …. !

Blackie doesn't deserve to go with just a couple of faint, non-specific memories and a few fond smiles, plus a golf tournament, so let me tell you about Blackie, probably the damndest, ballsiest, most unforgettable character I've ever known, in a career filled with such people, a guy at whose feet can be laid the rarest (and, to my mind, the best) compliment: “He sure as shit made life interesting!”

****************************

Blackie was not an Only Child, but close. He had a couple of sisters, older than him, both married fairly early-on in his life. His father had been an educator who'd done very well for himself and his family before dying when Blackie was quite young. That mean that Blackie and his mom co-existed in a very large house, large enough that Blackie told me that he'd occupy one bedroom until it was uninhabitable, then move to another, and repeat this process until the only thing left was his mom's bedroom, then he'd invite in his friends, and go on a weekend orgy of bedroom cleaning (on a truly grand scale) before starting the cycle all over again (Tom Sawyer could've taken lessons from him).

Not that he stayed in one of his various bedrooms all that much: he had a nocturnal escape route from each and every bedroom, and was liable to come and go at all hours. Yep, even at that age, there was no holding Blackie down. Between his after-hours tours and his occasional weekends visiting one of his sisters in posh Sun Valley , the lad definitely got around.

Somewhere in there, Blackie spent time in a military school. After all these years, the details have been lost in my mind, but I was later to see that the more useful aspects of that period were not wasted on him.

For instance … somewhere in his late teens/very early 20s, Blackie joined the Army. This was in 1957, and that's important, because he ENLISTED, for three years of active duty, at a time when the regular Basic Training camps were crowded with guys avoiding the two years of the draft by doing six months of active duty, along with 5-1/2 years of active reserve back home. Blackie knew that, when his three years were up, the other three years commitment was Inactive Reserve, and perpetual exemption from the Draft. Not only that, but he got to choose his service school.

Good thinking, hmmm? Same damn thing I did, the difference being that I intended being a career soldier, and he planned on being anything but.

Let me give you another, better illustration.

Basic Training, at that time, was eight weeks, plus what was euphemistically termed a “Zero Week;” in effect, a week that didn't count toward the 8 weeks of Basic. Blackie was sent to Fort Ord , California , not exactly a garden spot in the summer (at the same time, I was playing in the swamps of Ft. Polk, LA, shooting armor-piercing rounds on the firing range).

In the latter part of Week #6, a sergeant asked for a volunteer for duty at the bivouac site, helping set up the cook tent, digging the garbage dump, etc. Now, for those of you who've never been in-or-around the Army, you must understand two time-hallowed Army traditions: First, you never volunteer for ANYTHING. In this second tradition, “Bivouac,” you marched 20 miles carrying everything you needed for a week on your back, plus a 9 pound rifle, 2 pound helmet, plus a few other things, and lived in a pup tent (max size: two guys who had to act like close friends, even if they were total strangers: each of them owned one half of the tent, a piece just large enough to wrap up in if you couldn't find a buddy). Then you'd practice such creative games as field sanitation (digging slit trench toilets), maneuvering, camouflage, and other things that are always fun in the middle of the summer.

Now, by this time, everyone around Blackie knew what a goldbrick he was, a “goldbrick” being someone who was very good at getting out of work. Thus, you can just imagine the shock when the sole hand that went up belonged to … Blackie.

Despite privates' opinions, sergeants rarely reach that rank because they're fools; this one certainly wasn't, and grabbed Blackie in a flash; on Sunday morning, as the troops lined up to head out for the bivouac site, the talk was all of Blackie actually volunteering for something, and WHAT a something!

They all figured the sun had baked Blackie's brains, and probably held that belief right up till the minute they marched into the bivouac site, after hauling about 60 pounds of goodies on each of their backs for 20 miles in the middle of a sunny, hot California day … to find Blackie ensconced in the shade of a commodious tree, having a nice iced drink to go with his early supper, his tent site already staked out on the most desirable location. Seeing him like that probably coincided with the sickening realization that Blackie had NOT marched 20 miles out there, lugging his military life on his back. Instead, he – and his impedimenta – had ridden out on the back of a shaded truck, there to perform no more than two hours of honest labor.

It takes much longer than two hours to march 20 miles, even without a load.

That was typical Blackie: Creative Goldbricking.

************************

Blackie and I ended up at the same military school, the Army Information School at Ft. Slocum , NY . Both the school and the Fort are gone now, but they were as unique as was Blackie. The fort was a 17-acre island in the New Rochelle Yacht Harbor . The school was elite, with about as eclectic a student body as you can imagine: Army, Air Force, Canadian Air Force, students from half a dozen foreign countries scattered around the world, officers from lieutenants to colonels, NCOs, enlisted personnel, men and women, high school grads to PhDs.

Give you an idea of this student body. My roommate was, so far as I've ever been able to determine, the very first black television announcer in the world, Les Parker (a UCLA grad, in 1957 the only job he could find in the field was as an out-of-sight booth announcer .. in Montana). One of our next door neighbors was a Foreign Service Officer doing his six months of active duty. Upstairs was an ancient Master Sergeant wearing the West Point crest; I suspect he was the legendary Marty Maher, who was portrayed by Tyrone Power in Maher's film biography, “The Long Gray Line.” Down the hall from us was a young black with a Doctorate in Philosophy from NYU, and the unlikely name of John Quincy Adams.

The only Jewish kid in our class volunteered (and was accepted) for the only opening in Egypt . As he said, “I just couldn't resist the challenge!” This was some years in advance of Egypt making friends with Israel . And Steve LOOKED Jewish, too.

Obviously, Blackie and I fit right into this mixed but homogeneous mass.

Strangely enough, I didn't actually meet Blackie until our last day at Ft. Slocum . I'd heard rumors, mind you, but had not had contact with him, because we were in two different ivy-covered wings of the dormitory/barracks, and two different class sections. We had heard of each other almost of necessity: there were 164 men and women in the (psychological warfare) school and, of the 150 who finally graduated, only eleven of us were broadcast specialists: same training as the rest, and some demonstrated civilian experience, plus the ability to pass a few extra tests, none of which could be bullshitted: you either knew the subject matter or you didn't.

We nine did (two didn't, and ended up as heavy construction machinery operators, probably making more money in their lifetimes than any of the nine of us survivors ever did).

Although life in school was considerably looser than life in Basic, there was still a little military BS, mainly from what is termed the “support” structure: supplies, cooks, MPs, etc. Supply corporals are the worst: they've already figured out what the rest of their time in the military is going to be like and, as a result, they become bureaucrats and sticklers for detail of the first water, real pains in the nether regions.

I mention this only because our orders from Supply that Saturday morning were both precise and detailed (and representative, probably, of everything wrong with government service). At 8 a.m. EXACTLY, we were to be dressed and ready to go. We were to line up down a particular stairwell in strict alphabetical order. In our arms, our used bedding, neatly folded (despite the fact that it was going straight to the laundry from the Supply Room). As soon as the student before us had cleared the Supply Room window, we were to walk up to it, giving our name, rank and serial number in a crisp, military manner, and proffer to the supply corporal our used bed duds. (When I saw John Belushi checking out of Joliet State Prison in “The Blues Brothers,” it looked familiar: then I remembered checking in bedding at Ft. Slocum ).

We started promptly at 8:00 and, ‘long about 8:25 or so, we heard a faint commotion from the third floor, which gradually got closer and closer to our spot in the basement, until we could begin to make out words .. not that they made any sense. “Make way! Make way, you toads! You fools, make way for Emil Brewer the Goat Man!” etcetera.

Yep, it was Blackie. He was considerably late (since his last name began with a “B”: he should've been about 5 th in line at the outset) and QUITE out of uniform. More precisely, he wasn't wearing a uniform: he was clad in nothing but undershorts and a t-shirt, his hair not even combed, not a shoe or a sock anywhere close to his feet. Still bellowing his Emil Brewer litany at the top of his lungs, he elbowed his way past us down the very narrow stairwell, his still-warm bedclothes a mangled wad in his hairy arms.

Reaching the bottom of the steps, he marched briskly up to the Supply Room window, popped to a rigid position of Attention, recited his name, rank and serial number in as crisp a manner as you could ask and just shoved the unfolded wad in his arms into the arms of the supply corporal who, open-jawed, stared at this apparition as it did a neat military about face (which ain't easy in bare feet on cold concrete) and marched back up the stairs as if John Philip Sousa himself was accompanying the retreat.

*****************

Blackie had organized himself quite a bit better by the time we ran into him at the coffee shop an hour later. We got there about the time he started organizing a male/female glee club, teaching them a song of his own creation called, “Ho, hum, So What, I Couldn't Care Less,” which he'd written about the joys of the little island on which we'd spent the last nine weeks.

Then he took us touring around the island, ending up outside the window of the Post/School Commandant, where we bellowed our, by now, rather professional rendition of the song.

The First Sergeant came out and suggested we Take It Elsewhere, lest the Commandment develop a mental block while signing diplomas.

A short ceremony, and we parted for the next month.

Next stop: Korea , by way of Oakland , Hawaii , Wake, and Tokyo .

We arrived, by various routes, at Oakland Army Terminal, CA, in the late morning of January 2 nd , 1958 . Just about the only thing you could count on there was that almost everybody you met was on their way to Somewhere Else. The place existed only to process bodies passing through. The guys we felt sorry for were the ones heading for a little spot out in the South Pacific: “No civilian clothing. No cameras. No portable radios. No tape recorders. In fact, if the Army didn't give it to you, you can't take it with you.” We recognized the name of the place as belonging to a location where occasional world-class “booms” were heard, accompanied by very, very tall, mushroom-shaped clouds.

As for our little band of brothers ….

The first thing our tight-knit group did was compare orders, to discover that eight of the guys were heading for AFKN, the Armed Forces Korea Network, an entertainment/news broadcasting operation, AM and TV, headquartered in Seoul, but with small contingents scattered to hell and gone all over the southern Korea peninsula.

As for the other three of us …. Blackie, a proper Back Bay Bahstonion named Paul, and I were heading for something with the deliberately obfuscatory name of USA B&VA PAC DET, which none of us ever heard of.

No one else ever had, either.

A number of rather interesting things happened at Oakland , over and above the ubiquitous “short arm” inspection (standing there stark naked, a doctor's thumb pressed against your scrotum, and the instructions, “Turn your head and cough.” If you had a hernia, it immediately made itself known. The poor docs conducting this exercise had to cope with our embarrassment-fueled attempts at humor: “What did you do in the war, daddy?” “Why, I was a pecker-checker, son”).

We had to deal with the problem of what's called “extra duty.” In a facility such as Oakland, transients (us) are fair game for every crappy little job that the Permanent Party wants to avoid, things like working on the coal pile, collecting the garbage, washing the windows, unloading trucks, bagging groceries in the Commissary, etc. The saving grace here, for the Creative Goldbricker, is the sergeants supervising this nonsense are, themselves, transients, with no idea who in hell we were or who their peers were, either. This means we could keep a mop and bucket, or a broom, handy and, when we heard the unmistakable stentorian tread of a sergeant's footsteps in the hallway, leap out of our beds, where we'd been reading or catnapping, and grab our handy utensils. When that striped worthy waltzed in to say, “I want you five men for a garbage detail!” or some such, one of our number would say, “Gosh, we're sorry, Sergeant, but Sergeant (muffled sound, vaguely resembling a name) said if we didn't get this bay cleaned up, he was going to have our asses.”

Mutters and then the sergeant would depart and find five guys not quite as up on their psywar tactics. We'd go back to bed.

Write these things down, since they work in civilian life, too. First, if you want to get from Point A to Point B without being hassled, find a clipboard loaded with papers (even if blank), and walk head-down, with a serious look on your face. Muttering distractedly to yourself helps, too. People will automatically assume you're on A Distasteful Mission, and leave you the hell alone.

Second, if you confidently act as if you have every right in the world to be doing what you're doing, with no acting cute or covert, 99 times out a hundred, NO ONE will question your right to be doing whatever in hell it is that you're doing. They won't. It's human nature. If you want to keep a secret – in fact, to keep people from knowing there IS a secret – don't try to hide it. “Hide in plain sight” is the phrase often used.

We milked the hell out of those two guiding principles and, as a result, during our six day stay in beautiful downtown Oakland , not one of the eleven of us bare-armed privates pulled one single piece of extra duty.

Creative Goldbricking a la Blackie.

***************************

When I went into the Army, it was with thoughts of going to Germany ; unfortunately, I could pick my school or pick my destination, but not both. I opted for the school.

Most of my enlisted classmates (present company in this story excluded) wanted to either stay in the states (a.k.a. “The Land of the Big PX”) or, at worst, go to someplace with a stay shorter than the term of their enlistment … a place like Korea, for instance, classed as a “Hardship Post” and, thus, with only an 18-month posting.

So, naturally, the girls stayed in the states, and everybody else but us 11 went to Europe (ignoring Goldberg in Egypt ): we were heading East the hard way: by flying West. We were going to Korea .

Korea wanted us rather badly, for some strange reason. We'd gotten out of school in mid-December, and the original plans were to put our butts immediately onto planes to head to Frozen Chosen. Cooler heads prevailed. Probably fearing the first mutiny in the U.S. Army since the days of the Wild, Wild West, they relented and let us have both Christmas AND New Year's.

This meant, though, moving us along smartly thereafter.

In those days, such air travel was aboard an Air Force entity called MATS, the Military Air Transport Service, a not-too-bad airline, most of it with civilian-style aircraft, if not amenities (no booze, damnit!). Demand was high for space. Consequently, we were broken into three groups, the Other 8 into two, and Groucho, Chico and myself, Harpo, as a third. And, because of scheduling, we got bussed up to Travis Air Force Base, north of San Francisco , with the second of the other groups. The catch here was that they were leaving today, we weren't leaving until tomorrow but, because of bus schedules, we'd have to spend the night at Travis.

At last, we were on our own with no sergeants regimenting our every move. This was not a totally unmixed blessing because, now, it was up to us to find housing and dig up a meal. In this, Blackie was invaluable, the military school background having covered esoteric topics like that. So it was that, by 6:30 , we were settled in, our stomachs full – and Paul and Blackie decided to go out to see the town outside the gate. I chose to stay in, if for no other reason than to make sure all three of our butts were out of bed the next morning. I'd never been out drinking with these two before, but I rather accurately assessed Paul, despite his exclusive Bahston College background, as a naïf at alcohol consumption, and Blackie as only-too-experienced.

I also knew my limits (small) and pocketbook (flat, me having gotten married to a WAC, a classmate, in a largish Catholic ceremony during the Christmas hiatus).

With my blessings, off they went.

It didn't occur to me until later that I had every single copy of our orders. Why is this important? In the Air Force, the watchword has always been “Security.” In the shortest possible terms, getting off the base was no problem. Getting on, though, in the absence of either orders or a signed pass, was impossible.

“Impossible” was a word not in Blackie's lexicon. Its presence, in fact, didn't even stress him, nor concern him. He lived that kind of life.

Although it surprised the hell out of me at the time, I later came to almost matter of factly accept that Blackie had his own personal angel perched on his shoulder at all times.

Here's how it happened. Paul and Blackie finally settled in at a rather classy watering hole not too far from Travis. They were seated at the bar, and had downed several drinks, when an Air Force couple sat down next to them. This was a married couple, both in uniform, and both officers, stationed at Travis. There was an almost instant rapport between the Colonel (hubby) and the Major (wifey) and my two potential exiles: Blackie was fun to party with.

The four of them got totally loaded, at one point Blackie even mopping up a spill on the bar with the Colonel's cap, a move their quasi-hosts totally missed.

Since the next day was a work day for the Air Force's finest, it finally came time to break up the party – and my miscreants were offered a ride back to the base by their drinking buddies. This solved several problems at once. First, they were in no shape to walk the distance back. More importantly, with two uniformed officers in the front seat and an officer's badge on the front bumper, all the APs did was salute the car as it went through, checking not at all for passes OR orders.

My charges were not happy with me the next morning when I rolled them out of the sack, giving them plenty of time to throw up, clean up, and get some breakfast.

I took the abuse, figuring it was an improvement on trying to get them out of a military jail in time to make an Overseas Troop Movement, the missing of which was a court-martial offense.

(I can hear him in my ear now, “Pry, you ass, get to the POINT!” Not this time, Blackie: my crayons and I'll damn well color outside the lines if I want to).

Getting on the plane, hangovers and all, had only one minor hitch in it. I was asked if I would sponsor a dependent.

Hmm?

Yeah, seems that every dependent being transported overseas had to have an official sponsor along for the trip, to provide necessary physical assistance, unsnarl military red tape, etc. My reluctance must've been on my face, because I was given a short speech containing a strong implication that, if I said “No,” there might be some problems found with my travel orders, so I bravely volunteered for the duty.

See, the problem here was, that since I had the orders, I signed all three of us in for the flight: I was the only one of the 3 Stooges to actually be at the counter. If I'd had any smarts, I'd have given them Blackie's name (I'd love to have seen how he handled that conundrum) but, instead, gave them mine, and shortly thereafter found myself in possession of one Tennessee housewife and her two kids, one a babe in arms, and their voluminous hand luggage (including the Used Diaper bag), struggling them onto the plane, while holding a mental picture of me doing this all the way across the Pacific in a four engine propeller plane, the military equivalent of the venerable DC-7B, the last large prop airliner.

Paul and Blackie avoided me like the plague, “Pry, you ass, why didn't you just say ‘No!'?” Well, it's not that easy. “You've got no balls, Pry!”

Details lost in the midst of time but, somehow, before we reached the halfway point to Hawaii , this nice old Marine sergeant found himself with a Tennessee housewife and her two …. I was still her official Sponsor but, somehow, he ended up with guardianship of the three of them, which was fine by me: possession is 9/10s of the law.

“Slick move, Pry.”

High praise from a Jedi Master of No Force/No Foul.

********************

I wish I could tell you how long that trip took but, between time zones, the International Date Line, and resetting our watches to local time at every stop, it would take an MIT mathematician to work out the details. What I do know is this: we finally got off the ground from California just before 11 a.m. , after having had to wait for the fog to clear.

We arrived at Hickam AFB, Honolulu , right around midnight , and took off again about 3:30 in the (adjective censored) morning. We had breakfast at Wake Island , the Pimple of the Pacific, actually two atolls with a pond between them, and about large enough for two runways and a few buildings (God, what a deadly, lonely duty post THAT must've been). We left Wake around 10 and landed at Tokyo International Airport at dusk, just in time for rush hour.

These things happened during that period:

I had one of my few laughs on Blackie. While he and Paul were out scouting for an NCO club still open at midnight, I went to the Hickam MATS Coffee Shop where, shortly, I found myself sitting at a table with an older WAF and her charges: six young ladies from one of the out islands who were on their way to Lackland AFB in San Antonio for Air Force Basic Training. The three hours went by all too quickly in the company of these bright, excited, cute as hell wahinis, none of whom had ever left the Islands before.

My two traveling companions had walked the base, alcoholically fruitlessly, while this “old soldier” basked in the admiration of the hula girls, in comfort. When Blackie heard that, and saw the girls waving me goodbye as they proceeded to their plane, he wouldn't speak to me for several hours, except to hiss, “Pry, you ASS!” (Had I been younger, I might've come back to the states thinking Uass was my last name, after a year+ with Blackie).

My first realization that I had honest-to-God left the land of my birth came about 5:30 that morning when, having difficulty sleeping, I went back to the galley and got a carton of milk out of the refrigerator. Leaning against a bulkhead, I idly read the labels on the ½-pint carton. It was your standard commercial dairy carton, from a Hawaiian firm, with the standard blurbs on it … with one small addition. Underneath the “Vitamin D Fortified Grade A Milk” block was one small word, in parentheses, in teensy tiny type (no more than 4 points, if that). Like I said, it was just one word that put the whole trip in perspective: “(Reconstituted)”.

It was made from powdered milk, and I suddenly realized that I had already drank the last truly fresh milk I was going to taste for a long, long time (and, in fact, milk shakes in the service clubs in Korea were made from one gallon tin cans of whole milk, imported from the states).

It was chilling. One lousy word …..

I wasn't Home any more, Toto, and wouldn't be for another 16 long months.

*********************************

After breakfast and refueling at Wake, we took off about 10 (local time), this time with me seated next to Blackie. In his take-charge way, he announced that he was going teach me how to play his favorite two-handed game, Buck Euchre.

The fact that it was the first AND THE LAST time I ever played Buck Euchre in my entire life could probably be laid to the fact that we played all the way to Japan, at a guess about 8 straight hours, and I lost EVERY SINGLE HAND to this cardsharp, especially frustrating to this pretty good card player.

Blackie enjoyed the marathon tremendously. I wonder why?

********************************

A couple of large, commercial-type busses picked us up outside the terminal at Tokyo International and, no sooner had we moved into the rush hour traffic (just as heavy in Tokyo as anywhere else in the civilized world), than Blackie started screaming. “DRIVER, STOP THE BUS, STOP THE BUS!” The Japanese driver started to slam on the brakes about the time Blackie added, “YOU'RE DRIVING ON THE WRONG SIDE OF THE ROAD!”

For the uninitiated, the Japanese drive on the left side of the road, British-style.

The driver was muttering as he moved his foot back from the brake to the accelerator. (I suspect it was the Nipponese equivalent of “Crazy mutha!”).

Blackie was fairly quiet after that spasm, as we took in the sights – including the six-year-old standing unconcernedly at the edge of the crowded traffic, calmly and unashamedly urinating on a telephone pole. In fact, the only comment I remember out of him came when we were stopped at a light, a city bus loaded with commuters next to us. Blackie's dismissively straight-faced comment after looking over at it, “Hmm .. there are an awful lot of foreigners around here.”

Blackie could trade non sequitirs with the best of them.

**********************************

We caught up with our classmates at Camp Drake , outside Tokyo , to discover that our little campaign back at Oakland had borne fruit.

We'd started a rumor.

Those pieces of brass worn on Army uniforms are NOT there just for decoration. If you look closely at those round pieces worn on the lapels, you will find insignia denoting the branch of service of the wearer (crossed signal flags for the Signal Corps, crossed rifles for the Infantry, etc.) Now, it would be impractical to have a different piece of brass for every minor specialty (and thank God: I shudder to think what the Pecker Checkers' brass would've looked like – crossed WHATS?!?), so there are a few generic ones. In our case, we wore just the eagles – the same as the Army's criminal investigators wore, so we just started a rumor that there were three groups of undercover CIC (Criminal Investigation Corps) agents on their way across.

That was the one and only lie we had to tell in order to have the desired effect. Use minimal force for maximum effect.

At Camp Drake , troops were housed in squad rooms or “bays,” each one big enough for twelve men. Before we got to ours (more than ready to hit the sack), we were reminded that we were still in the Army. “You men will be responsible for the cleanliness of your bay and your uniform. There will be a rigorous inspection each morning!”

Yeah, right. All eleven of us were put in the same bay, the last bed left vacant. While the rest of the bays got a fairly rigorous going over each day, our inspection consisted of a junior office sticking his head in the door each morning, doing a 90 degree sweep of his head, quickly, before hurriedly saying, “Looks good, men!” and then beating a hasty retreat.

We pulled not one lick of extra duty, despite our obvious availability – and, remember, we had not one bit of rank between the eleven of us.

And we didn't have to lie .. but there's telling the truth, and then there's telling the truth in such a way that it SOUNDS like a lie. “Trooper, are you CIC?” “Me, sir? Why .. no .. sir, why would you ever think that?” accompanied by vague smiles by the entire lot of us; a small, muffled snicker from the background didn't help the believability of our denial. Blackie was a past master of both moves.

In the presence of the cops, even nuns feel guilty.

***********************************************

It was Blackie who, the next night, got us into Tokyo proper, and into our first Japanese night club, pretty much the same as the U.S. variety, except brighter, cleaner, and noisier. My true introduction to the culture, though, actually came as I was standing at a urinal, doing what one does at that porcelain fixture, when a very attractive young Japanese lady walked by me, smiled, and said, “ Ohio ,” their equivalent of “Hello.” I knew that already, else I might've replied, “ Arkansas !”

With my manhood in my hand, all I could do was smile weakly and nod my head as she passed unconcernedly on.

Apparently, the Japanese had invented the unisex bathroom before we'd ever heard of such a thing.

***********************************************

Prostitution exists in Japan . It is not legal, nor is it flaunted, but it's there. A cathouse and a Geisha house are NOT the same thing. A geisha is not necessarily a prostitute – in fact, if she puts out at all, it's as a minor part of her main job, which is to flatter the living hell out of a man, to be decorative, sweet, and to leave him with the impression that she absolutely adores him, his looks, and his mind, to make him FEEL like one helluva man without the necessity of him PROVING it.

Of course, there is a certain amount of crossover here in attitudes, since the average Japanese prostitute makes you feel that way, too, with quite a bit more physical involvement. Your standard American street hooker is a pallid playmate next to these exquisite ladies.

I mention all this merely as background to the fact that, on his first night in Tokyo , not being at all conversant with either the culture or the language, it was Blackie who found us a cathouse. In my innocence, I thought he was checking us into a nice but unspectacular hotel. This was before I found out the room came with hot and cold running … uh .. amenities.

Later in the evening, Blackie's amenity was heard, through the thin wall, saying with some asperity, “You go sleep now. And you go sleep, TOO!”

Blackie had no company in the room other than the young lady. You figure it out.

******************************************

We would party every night till about midnight or one, getting back to Drake in not too steady condition. You will understand, with that information, the kind of shape we must've been in when they woke us up at 4 in the morning with the hot news that it was time for breakfast, this preparatory to our departure for Korea.

As the late writer Roger Hall said of an identical situation, “Morning was Death, with songbirds.”

Tachikawa Air Force Base was a pretty little place, with a nice little MATS coffee shop. At the time of our arrival, we had neither the time nor the inclination to appreciate either. Instead, we aroused ourselves from our torpor just enough to line up for the trek out to our airborne conveyance, which was a Douglas Globemaster. You may have seen pictures of these ungainly beasts. They looked like overgrown Greyhound buses: very high bodies, high wings, what looked like a black nose at the very front, and clamshell doors that opened beneath it. With the windshield above it, when the front doors were open, the plane looked like it was offering us a very malevolent grin, a not-inappropriate symbol.

I go into this in some detail because we were to become intimate friends with that damned plane over the next few hours. The Globemaster was a double-decker, we saw as we clambered on board, and could hold so many people that our nickname for it was “Crowdkiller” because, when it went down, it took a crowd with it.

In this instance, the bottom deck was loaded with heavy machinery, and we had to climb up a ladder to the upper deck, which consisted of a metal floor with lots and lots of holes in it. Our seats were canvas stretched over metal rods, paralleling the outer skin of the plane, the interior of which we could easily see, since there wasn't a bit of insulation or soundproofing inside that thing.

The tone for the trip was set when an AF sergeant went to the very front of one of these rows of seats and suggested that the kid there might want to move someplace else. Now, in the military, as elsewhere, there's a certain cachét to being first in line (although it hadn't occurred to the kid that he'd be last off), so it was with a certain amount of suspicious hostility that the kid asked, “Why?!?” “Well,” the sergeant said laconically, “every once in a while, the propeller'll come off one of these engines and, when it does, it usually comes through the wall right about where you're sitting.”

The kid moved, rather quickly, as I recall.

We thought the beginning of our trip was inauspicious, but we hadn't seen anything yet. It was to become what Blackie later described (the first time I'd ever heard the word), a “.. monumental clusterf**k.”

Besides a planeful of world class hangovers, compounded by not much in the way of sleep, the trip beginning matched the internal feelings of the passengers.

The engines started, but there was something about them the pilot didn't like, so we thereupon all got off the plane and, this time, adjourned to the nice little Tachikawa AFB Coffee Shop. We managed to fill ourselves with coffee, which did a surprisingly good job of bringing us to some stage of consciousness an hour later, when it was time to climb aboard our chariot again, by tacit agreement everyone pretty much plunking themselves down where they'd been the first time.

Engines started. This time, we managed to taxi out to the runway where, after a certain amount of futzing around, the pilot decided he STILL didn't like the engines, so he taxied back to the terminal, and we got off again. To the coffee shop, this time for brunch.

Understand that, with food and coffee in us, the soldiers' time-honored tradition of being able to bitch was being honored, in spades (please understand that griping is a fair measurement of a unit's mental health: the more bitching, the better. It's when a group is so demoralized that it can't even gripe anymore that you are in deep doo-doo; I've been in that kind of unit, and it's not fun).

Then, once more into the breach – uh, the plane – dear friends. By this time, with food in our stomachs and maybe 3 hours of sleep under our belts, we got into our seats, fastened our belts and, as soon as the plane started its take-off roll, started dropping off to sleep.

This was a sleep that did not last long, if for no other reason than, 3/4s of the way down the runway, 3 of the 4 engines quit cold. This got our immediate attention. When I looked up, there were a lot of buildings whipping by the window very fast, and there was a lot of brake squealing (and praying) as the pilot finally managed to get that monster stopped, about ten feet from the end of the runway. As I recall, the next thing past the end of the pavement was a lake.

Taxi back, get off … and, this time, before reaching the fence to the terminal, all of us turned around to memorize the tail number on that huge, cumbersome beast. Surely, NO ONE in their right mind would put us back on that damn thing!

Right mind? Sure. But, the MILITARY mind is another creature altogether and, when we got our boarding call again, to find the same damn plane waiting for us, there was an immediate identification of all Catholics in the group, because of the Sign of the Cross stuff going on. We Protestants found ourselves a bit jealous for not having any such ritual handy.

Incidentally, in case you're wondering why I haven't quoted Blackie yet, it's because he said nothing printable: interesting, yes, but much too profane for a PG or R rated blog.

Onto the plane and, this time, as we began our takeoff roll, all of us were gripping the bottom frame of our seats, tugging up, as if by doing so we could help the plane into the air. It – or something – worked because, at long last, we had that indefinable sensation of honest-to-God flying.

We cheered, loudly and for some time … which was fine, except that, as our cheers died away, we could hear the CREW cheering up in the cockpit. Hardly reassuring.

Having burned all our adrenaline allowance for the month, a surprising number of us laid down on the hard steel floor and went to sleep.

It was dark when we landed at Kimpo AFB, outside of Seoul . It was also bitterly cold, as only Korea can be, with Mongolian winds funneled by mountains right down the full length of the peninsula.

It was also snowing, as it turned out, the start of a monumental blizzard.

Our morale, already in the crapper, was not helped by being unloaded in front of the old original admin building on the base, you know, the one with all the machine gun bullet gouges in it.

It was at this moment, at that place that, for the very first time, I heard a phrase which has now become a clich é , Blackie saying in tones of almost unbelievable disgust, “If God ever decides to give the world an enema, the nozzle goes right here!” It sounded almost like an order to God, rather than just an observation.

*******************

Ascom City (if I'm remembering the name right – I have a tendency to DISremember places and/or people I despise) made Oakland and Camp Drake look like luxury spas. It was the main “repple depple” (replacement depot) for Korea, complete to unfinished wooden barracks containing oil-fired heaters totally inadequate to the task, and with no social amenities whatsoever, plus a cookstaff that figured they were never going to see any of us ever again, so why bust their butts cooking something with flavor to go with any residual nutritional value.

This would've been bearable if we'd only had to stay there a day or two, but that snow that had started when we landed had gone on and on, in wholesale lots, to the point where all normal transportation went down the tubes. Our eight buddies finally got out only because some creative types at AFKN had commandeered a vehicle that could get through the snow, both to pick up our guys and, NOT coincidentally, to drop off some of their people going home (thus making our buddies' appearance doubly important).

We caught up on our sleep, though, since the only place you could stay warm was in bed.

Chickenshit still avoided our little group: it was the other guys who had to go out in the snow and get POL (Petroleum, Oil, Lubricants) for our laughable heating stoves.

Somewhere in there, though, there was one interesting little exercise. We were told to haul our stuff to a warehouse. There, we had to turn in all our “Class A” uniforms, our dress uniforms. As it turned out, we were in the last basic groups to be issued the old brown Army uniforms, complete with the waist-length “Ike” jacket. However, even if we'd had Greens (the new uniform, at the time), we'd have STILL had to turn them in, because they were definitely off-limits for enlisted men in Korea .

What we were given in their place was called “OGs,” (Olive Greens), kind of like fatigues, the time-honored work uniform, only these were in wool worsted.

We did not complain about this, since they were a helluva warmer than cotton.

After almost a week of this, we heard a rumor that some general was sending a vehicle to pick up his enlisted aide, who'd been on R&R (Rape and Recreation – well, okay, actually Rest & Relaxation) in Tokyo, and the general wanted him back, and had the rank to make that happen.

We found the subject EM and gave him a sales pitch to let us go along. He spent some time on the phone before saying “Yeah, but …” the “but” in this case being that the general was sending a one ton truck equipped with chains to get this irreplaceable young man, meaning we'd have to ride in the canvas-covered-but-open-end back of the truck.

We were so desperate, we took it.

The only thing notable about the trip itself was that we got colder than any of had ever been in our lives .. and probably the only thing that kept us from freezing to death was the fact that one of the smaller chains on the left rear tire had come loose at one end, so that it was hitting the inside of the fender several times with every high speed rotation. At first, it was irritating as hell, then it slowly got through to us that there was a definite, intricate rhythm, a very catchy one, to this, and we spent a goodly portion of the trip wondering how you signed up a tire chain and a fender to a recording contract. I mean, would the driver have to be given royalties?

This kept up until we froze into immobility.

*************************

Our driver had no more idea of where in Seoul we were supposed to go than we did, even if our eyelids HADN'T been frozen shut. Since the indecipherable alphabet soup of our unit (USB&VA Pac, FE Det) seemed to be of a kind with the initials of KMAG (Korea Military Advisory Group), that's where he decided to drop us.

Not LITERALLY drop us: we would have shattered.

We staggered into a WARM MARTHA WARM Orderly Room, with a sign on the wall, “Welcome strangers, especially replacements.” The duty sergeant was delighted to see us – until he took a look at our orders, muttered an appropriate imprecation, then picked up the military phone book and made a call.

He generously allowed us to thaw at his stove.

A deuce-and-a-half showed up; this is one of those really big whunkers: tandem rear wheels, and tires that looked like they could carry the truck, loaded, vertically up a cliff. It looked like we were going to have to ride in the back of the bus again but the bright, smiling young man who'd picked us up (his sleeves as bare as ours) defied all military regulations by insisting that all of us get in the front seat. It was a tight squeeze but, My God, it was WARM MARTHA WARM!

As it turned out, our new home was not that far away but, significantly, outside the 8 th Army compound, in a small, reasonably neat compound of its own …. right across the MSR (Main Supply Road) from the dismal-looking 8 th Army Stockade, the military equivalent of a penitentiary, but without free gym equipment, cable TV, conjugal visits, and the rest of that nonsense. The guests there, as we pulled into “home,” were outside in the snow doing close order drill and, judging from the condition of the snowpack, had been doing so since lunch or thereabouts. We never did figure out if our unit being located where it ended up was a not-too-subtle reminder from 8 th Army that we weren't entirely bulletproof. If so, we missed the point, and watched with great satisfaction in the spring as a brand new NCO club was built right up the hill from our place.

Our host explained a few things to us when we entered one of the Quonset huts (these are those metal buildings that are all arches: only the vertical ends are flat), the one designated as our barracks.

He did not have to explain that it was WARM MARTHA WARM: that was self-evident … although there was a cruel sort of justice in the fact that the shower room was located in the only concrete building in the place, halfway across the small compound, nearer to Officer Country (we had two of them, which will give you some idea of the relative worth of EM vs. officers. Remember M*A*S*H? “Is this an officer or an enlisted man?” “Enlisted man.” “Put in larger stitches.”).

We were part of United States Army Broadcasting and Visual Activities, Pacific, Far East Detachment, better known as VUNC, for “Voice of the United Nations Command.”

The radio tower we'd seen down in the rice paddy belonged to us. Besides a very active print organization downtown in the KBS (Korean Broadcasting System) Building, preparing materials for distribution by the Korean military (ROKA, or Republic of Korea Army), we broadcast 19-1/2 hours a day on AM and two different short wave frequencies: one hour of English, 18-1/2 hours of Korean, Cantonese, and Mandarin, running from 5 in the afternoon until 11:30 the next morning. The “Test Hour” (in English) was both for self-aggrandizement, and because all Koreans who'd reached school age around the end of WW II (you remember that one: it was in all the papers) knew how to read and write English, but damn few of them knew how to pronounce it.

They loved American music, though, especially orchestras and Broadway musicals and that, by God, was what we gave them – with no direction from anyone any higher up the food chain. The inmates literally ran the asylum, the Major in charge of the whole outfit being a somewhat more polished version of Blackie: minimum force for maximum effect … or, to put it another way, tell them what end result you sought, then trust these bright, well-educated young men to know what they're doing and how in hell to do it.

A very refreshing attitude that showed itself in strange ways. For instance, it was made abundantly clear to the Zebra Derby (all those sergeants and their stripes), that the Enlisted Barracks were our homes and, should the sergeants happen to go in after hours or on weekends, they were there as our guests, and were to go effectively blind and deaf on anything that smacked of being against regulations …. like the locked refrigerator full of beer, or the magnum of sak é sitting on top of the heater at our end of the hut (both of which were Blackie innovations).

The major, of course, was not above deliberately making us sweat a bit. “What's in the refrigerator, Blackie?” “Uh, cokes, sir.” “May I see inside it?” “Well, sir, the only key is in the hands of Dummy (our deafmute Korean houseboy), and he's gone to the village .. sir.”

The major just smiled and moved on; he knew damn well what was in it, and just couldn't resist giving our collective tails a little jerk; besides, it was part of his assessment of his troops: how creative can they be when pinned against the wall?

VUNC stayed but, later, the USA B&VA PAC, FE DET became USA B&VA FE, KOR DET, which is a kind of self-explanatory acronym. This occurred when our headquarters moved to Okinawa from Tokyo , leaving our two operational detachments behind in place. The practical aspect was to put one more layer in the trail our promotions followed down, so that it ended up as Washington to Ft. Bragg, to Okinawa, to Tokyo and, finally, to us. If there were anything left by the time every previous stop had siphoned off the ranks they wanted, we got them.

This means that, at best, we were ALL PFCs (Private First Class) – not that you could tell, really, since none of us wore any rank whatsoever, just a UN neckscarf with “VUNC” embroidered over the crest. (One of our overloaded jeeps was stopped by an MP one day, a guy who told us he'd been watching our vehicles for a year-and-a-half and was getting ready to go back home, but he just HAD to know what the alphabet soup on our bumpers meant).

This is where we first learned the oriental concept of “face:” had we made it clear to the high-ranking government officials with whom we routinely dealt that they were dealing with the bottom of the Army's food chain, they would have been highly insulted. With no rank showing at all, and us introducing ourselves as “Mr. Such and such,” they could kid themselves that they were dealing with, at worst, officers in disguise or, better, civilians in uniform.

Got that?

We took to it like the proverbial ducks, especially since we quickly learned that we were now part of a “gray” propaganda organization. A “white” organization would've identified itself as “VUSA – the Voice of the United States Army;” on the other hand, a “black” operation could've called itself “Radio Peking 2” or some such .. ANYTHING but what it really was.

As a “gray” operation, we gave it a nice cuddly name and just let people draw their own conclusions. At no time did we make reference to the U.S. Army having any control over it.

Right up our alley: little misdirection never hurt anyone, right?

To make sure I leave nothing essential out, I have to do this last installment as a kind of pastiche , without a huge amount of detail or coloration.

While Blackie was always almost belligerently brilliant, he automatically knew when to take a lesser place as a tribute to someone's superior knowledge. That's a high-falutin' way of saying he knew when to shut up and learn something, as we learned from him.

Initially, Blackie and I were placed in Studio Operations, the five guys who actually punched the buttons and got things on the air. The first shift was the one that, live, had to combine the Tokyo signal and pre-recorded tapes sent to us from Japan, getting them both onto the air while simultaneously recording them on master tapes for use later that night and the next morning.

It was precise work, but nothing taxing and, usually, we were each at our two operational positions, feet up, reading our respective books, with our necessary moves signaled with a finger or a grunt. Blackie took his lead from me because, although younger, I knew this part of the civilian world cold. On the other hand, when some visiting fireman came through, the Major liked Blackie and me on, because we could make the whole process look like launch time in Houston . The major never said anything to us about our extravagant sham, but let us know he certainly enjoyed the show, with our terse, tense “Stand bys!” and “Roll one,” etc. His visitors always did, too.

Blackie and I enjoyed it while it was going on, then put our feet back up and went back to our books.

But it was Blackie who got permission from the Lieutenant to rearrange our section's work schedule; true to the Major's dictum, self-government was left to run amuck, with the result that Blackie came up with a masterpiece of scheduling. I mean, here are five guys responsible for making this operation work 19-1/2 hours a day, seven days a week, with one shift absolutely requiring two guys on.

How does two days on, four days off grab you?

*****************************

Eventually, each of us went on to other duties, our contact limited to after hours. Blackie got involved in writing and interviewing downtown, I wound up in, first, administrative duties, then studio production (one hour a day in English, two hours a day in Korean, with source material primarily from Japanese Voice of America tapes – a mélange about normal for our whacky unit).

Occasionally, we'd get caught up in each other's creative schemes, like maneuvering ourselves an entire record library from our friends over at AFKN. The Major was smart enough not to ask.

Other times, our contact was … shall we say, “recreational”? There was, for instance, the 4 th of July we were invited to a little bash over at the Stars & Stripes billet on the shores of the Han River (both the newspaper guys and we all being graduates of the same school). “Drunken Brawl” would not be an inadequate description. I vaguely remember being sworn into the Air Force by a young lieutenant, under the owl-gazed gaze of approval of a full bird colonel, both gentlemen (by act of Congress) having been classmates of ours back at Ft. Slocum.

I really don't know what Blackie was up to, not until the next morning, anyway. The Stars and Stripes crowd had, at some point, left their compound en masse and all went out to the Village to shack up with their respective girlfriends, leaving their official home to the bodies who'd been drinking their booze the night before.

Good thing, too. I woke up in their First Sergeant's bed, thankfully sans the First Sergeant. I found Blackie in the Day Room, the scene of the crime. Blackie was, quite literally, draped over the refrigerator, side to side, his head and arms hanging down one side, his legs down the other.

We recalled it as a fine party, and were quite happy to attend their New Year's Eve brawl. I remember even less of that one, except that my Korean driver got a bit concerned when he hadn't heard from me by one a.m. (besides which, he wanted to go home), so he came looking. He finally found me, curled up and asleep, in the S&S group's outdoor BBQ pit.

Don't ask, because I can't tell you. Memory can be kind.

******************

Understand something about guys like Blackie: you can't get away with the kind of crap with which he was forever getting away UNLESS you've got some substance to back up the BS. That this applied to Blackie in spades was a lesson sometimes hard won by his students.

I could do an entire book on our battles with our First Sergeant. Now, for those unfamiliar with the military, the “top” (as he's sometimes called) is the top enlisted man in the unit, the COs direct representative. He can make you or kill you, as a unit.

We lost a fine one when his wife gambled away their life savings on the ponies and then, unable to face him, filed for divorce. Well, he'd been married to the woman as long as he'd been married to the Army (20+ years), so we got hold of the Red Cross and had his butt on a plane to California within 24 hours. Technically, “Compassionate Leave” .. but we knew he wasn't going to be back: there was too much damage to be healed in that marriage to accomplish in two weeks.

So, we had to requisition a Master Sergeant from the 8 th Army pool: that was the sole requirement, other than knowing administrative work: he had to be a Master Sergeant (E7), which was the top enlisted rank at the time.

I'm not sure it ever occurred to the Major that, under those circumstances, what we were going to get was someone no one else wanted. If it did, knowing how his mind worked, he figured that either we'd straighten the Top out, or vice-versa.

We got …. A guy who'd been in the National Guard, had made all his rank there, without a day of active duty beyond basic training, and two weeks every summer. Now, NG duty doth not a bad soldier make although, in those days, the Guard (“Draft Dodgers,” “Weekend Warriors,” etc) were, in the main, more like the clichés the guard still suffers from today, unfairly. Probably a more accurate measure of the man (I'll be generous) was that he'd never been married, and the best he could work himself up to in his civilian career, was a supermarket checkout clerk.

He spent two weeks getting to be “our best friend” then, having taken notes copiously during that 14 day period, came down on us with both hobnailed boots en pointe . And on a Saturday night, too.

That was the night that both war was declared and the Top got his nickname and gender: “Mother.” That was a contraction, if you will, yelled loudly at midnight by the leather lungs of a self-proclaimed Honolulu dock rat named Marty. “Oh, mother …. Mother …” and then he uttered the complete word, and it seemed so appropriate that we never considered anything else for her.

The main elements of the battle were this.

Mother had an inferiority complex, based on several items. First, of course, was his Guard background. This was compounded by being not too bright in an outfit in which, almost by definition, just about everyone except the guys in the Motor Pool were very, VERY bright. For instance, one guy named Pete. Pete was about 6'3”, sandy, curly hair, and an open, almost goofy looking face. To put a point on it, Pete didn't look too damn bright at all. In point of fact, Pete spoke some six oriental languages fluently and colloquially, and his sole job was to load up a jeep with choice foodstuffs, and then go out on the economy for a couple of weeks, inviting himself in with various Korean families for a day-or-two at a time, paying for his keep with stuff from his food goodies stash, and using the visiting time to probe their attitudes on any of a number of subjects.

He was our one-man survey staff.

Mother declared war by deciding to regiment people like that with standard Army BS, the kind you pull on the high school graduates in a not-too-sharp service company. This attempted regimentation even included those of us in the studio section, with our weird hours, plus the guys who worked downtown, who were frequently out at night at various diplomatic functions, etc.

He/She would have had better luck attempting to regiment a pile of earth worms.

Mother decided that four of us, including Blackie, needed a little extra physical training so, on a heretofore sacrosanct Saturday afternoon, put us to moving a sandpile from Point A to a spot 12 feet away, designated Point B.

When she came out to check on our progress later, it was to find that we had modified our uniforms to match those of the miscreants lodged across the MSR in the stockade, rather embarrassing to Mother, since our work spot was right next to, and through the fence from, the new road leading up to the new NCO club, at which she was a frequent visitor (at least, until the night, some months later, when all the wheels disappeared from her jeep in the NCO club parking lot).

That took care of that type of extra duty.

Mother quickly identified Blackie as the Georgie Patton of our group of creative miscreants, and decided to make him a target of humiliation. Okay, kid, was a tacit challenge, you think you know more about the Army than me, I'll show you you don't.

If you ever decide to issue that kind of challenge, better do a background check.

Mother hauled our collective butts out for Saturday morning PT, split us into two groups, and archly announced that we were going to practice a little close order drill (translation to you civilians: How To March), with him taking one group and, “since he knows so damn much about it,” Blackie taking the other, designated the starting points on our abbreviated parade ground, and then off we went.

You kill drillmasters the same way camera and sound people kill TV directors they don't like: you do exactly what they tell you, no more, no less. You do NOT anticipate, you don't cover the occasional off-tempo command. By tacit agreement, that's what we did to Mother. We never failed to carry out a command (although there was some “innocent” confusion over what constituted the right foot and what the left), but we didn't look ahead, either.

In something less than ten minutes, we constituted a marching slum, crooked lines and all.

As for Blackie's group … remember my mention of that military school somewhere in his background? It came to full use and flower that morning. During the same period of time in which we'd become a mob with the component parts heading in roughly the same direction, Blackie had whipped his group, with crisp, sure commands, into such esoteric movements as countermarch (where you reverse direction, but in the same order as that you were in heading in the opposite direction), and even right and left oblique, where the whole damn group moves diagonally to its original line of march, before resuming a straightforward motion.

Looked like it was off the parade ground at VMI.

Mother's humiliation was complete when she noticed not just the rest of our NCO's standing to one side watching, but our officers, too.

That was the last Saturday we played military grabass. It also built a Hands Off sign around Blackie, at least so far as Mother was concerned.

****************************

Blackie was in a cathouse one night, in typical Blackie fashion, in the sack with what had to be the only identical twin hookers on the peninsula, when the MPs raided the place. While the girls were running around screeching “MPs! MPs!,” Blackie was calmly getting dressed.

There is this thing in the military called “Command Presence,” the kind of demeanor that makes it unnecessary to bark orders, since following them when they come from someone with CP seems like such a .. natural, logical thing to do.

Blackie had it, in spades.

When he came out of his room, on the 2 nd floor of the hospitality house, MPs were ringing the bottom of the stairs. Blackie walked calmly down the stairs, leisurely arranging his UN neckscarf, said, “Excuse me, gentlemen” … and walked right through the MPs, going out the back door to the hooch, and long gone by the time it got through to the constabulary that they'd just been Had.

THAT'S Command Presence.

*****************************

I only saw Blackie at a loss for words twice in all that time. Predictably, I suppose, they both involved gambling.

The first time was at the Rocker Four Club, an NCO club in downtown Tokyo . Blackie had ensconced himself at a slot machine at the head of a row, right across from the bar, a juxtaposition he found ideal. For a solid hour, he fed coins into that damn machine. He worked so hard at it that he worked up a thirst. He turned, walked six steps to the bar, and ordered a fresh drink.

When he turned to return to the machine, it was to find that someone had walked up to it right after he moved to the bar and, as Blackie watched in horror, the interloper hit the jackpot.

Blackie was not the same for several days thereafter, and conversation was nonexistent for the rest of that evening, as Blackie drank himself into insensibility.

The other time was during one of our legendary marathon poker games in the small Studio barracks. Eight guys were gathered around Blackie's bunk, on the head of which he sat like a non-slanteyed Buddha, presiding over our financial trashing.

Now, it was no secret to the group assembled or to myself that I'm a lousy poker player. It cost me an unbelievable amount of money in Korea to learn how (my mafia-waitress Grandma had taught me to shoot craps, but not play poker, an oversight I deeply regretted). But finally came one hand … one by one, the other six participants threw in their cards as it came down to a showdown between Blackie and me, at the other end of the cot, playing for the quite nice pot.

We finally reached the raise-raise stage, with Blackie – who had three identical cards showing – beginning to hiss, “Pry, you ass, get out, get out, you're going to lose your ass!” And I'd raise him again. He finally, after several repeats of his imprecation, called me.

Yes, he had 4-of-a-kind, and quite proudly began to reach for the pot when I laid out the only Royal Flush I've ever hit in my life. He let out a strangled grunt, an expression on his face as if I'd just hit him in the back of the head with a 16 pound sledge hammer …. Then wordlessly went out and walked around in the snow for a good hour, no jacket, just Blackie, muttering to himself.

As much as I thought of Blackie, I DO look back at that as a Golden Moment in our friendship.

“Pry, you ass, you have the damndest no-talent luck I've ever seen in my life!”

I love accolades.

******************************

At a time when the U.S. military was trying its damndest to get as many people out of Japan as possible, Blackie maneuvered a transfer to our Tokyo Detachment in lieu of returning back to the states. He was put in charge of a large writing/production group of mixed officers and civilians. Blackie wore civvies (civilian clothing) to work, it having been decided that everyone working for him might mutiny when they found out they were working for the lowest-ranking man in the group.

To the best of my knowledge, his group not only never found out, but it never occurred to them to question it.

As for his social life while in the Land of the Rising Sun .. I have no idea. I DO know that he returned to the states with enough money to buy a full race Corvette and go on a six month drunk of the western United States . This monumental binge came to an abrupt halt one night when he piled the ‘Vette into a bridge abutment at 65 miles an hour.

In typical Blackie fashion, he came out of it with a busted ankle and a cut on his forehead, although he had help: seat belts, which were NOT standard on most cars in 1960. As he put it in his most inimitable way, “If it hadn't been for the bad belt, man, I'd have gotten the wood.”

I went out the next day and had seat belts installed in my car, and there they've been ever since – and have saved MY corpus delicti a number of times so, in a sense, I owe my very life to Blackie.

(On the last tape I got from him, he told me he'd gotten a job as a cigarette company district representative and, oh yeah, “I may've damaged my head more than I thought: I'm getting married”).

That was my last contact with Blackie, 1961. Yet, you can tell that he has never been far from my mind. If this series of stories seems to be as much about me as about Blackie, there is a reason for it: during one of the two most formative periods in my adult life, Blackie was an integral part of that life, and a lot of me today is legacy of Blackie Then.

I'm glad that part of my personal belief system is that our souls get recycled. I find it very reassuring to think that Blackie is or will be back, puncturing the pretensions of assholes, and I'm sure that, when my approaching time finally arrives to take the Trip Through the Tunnel of Light, it will be to hear a voice hissing, “Pry, you ass, it took you long enough to get here. Come one, we've got work to do!”

![]()

It is not often that one gets a chance to watch an entire country's economy suffer a major disruption, but I had that opportunity, back in the 50s, in Korea . I've never seen this in print, and I figure some of you might find this interesting.

I was in the Army, in Korea in 1958 and part of 1959. As you can imagine, it was a rather strange environment to this ole Arkansas boy. It was particularly strange when it came to buying things. To purchase something did not always involve cash and, when it did, it was almost never any cash you'd recognize today.

For example, our weird little group decided we wanted matching dressers in our part of the barracks. We turned our houseboys loose on the problem, and they found a very good cabinet maker: three drawer oak veneer dressers, the top just the right height to double as our bedtable, all identical. The price? 2 cartons of cigarettes apiece. Our cost? $20. His profit? About double that.

Cigarettes were rationed (we got ration books every month), but pretty generously. American cigarettes – and Coca-Cola ™ -- were highly prized by the Koreans; if you've ever smoked a Korean cigarette or drank what purports to be a Korean soft drink, you'd understand why.

The Koreans felt pretty much the same way about our money, too: it was quite prized, WAY over and above the Korean Hwan.

What we were using wasn't even what my wife would call “real” money (a distinction she once made between U.S. and Canadian bills – while standing on the Canadian side of the border). “Greenbacks” and coins were not used. We were paid in MPC (Military Payment Certificates), colorful, fully engraved bills, printed by the Treasury Department, and available in all denominations, down to a nickel. Instead of U.S. presidents on them, I seem to remember various anonymous Roman and Greek soldiers on these mini-works of art.

The colorful engravings were NOT why MPC was so treasured. To understand, you must first understand a little economic nicety called the Rate of Exchange. You've seen it mentioned in the papers and TV: “The Japanese Yen fell again today against the dollar, which itself fell against the Euro …” In 1958/59, the rate of exchange of the Yen was 360. One dollar U.S. would buy 360 yen. This rate, last time I looked, is now just a little over 100 yen to the buck, meaning that, in real money, yen is worth about three times what it was 40 years ago. In practical terms, that $1.00 cup of coffee then costs an American $3.00 now.

Japan 's economy, while weak, was stable. That 360 yen was both the official rate of exchange (what you'd get at a bank, for instance) and the same as out “on the economy,” whether you were exchanging MPC or greenbacks. Bank, bar, money exchange, made no difference. One buck, 360 yen (or ¥ 360, if you prefer).

This was NOT the case in Korea . The official rate of exchange was 500 Hwan to the dollar, but the Unofficial rate of exchange hovered around 1800 and 1900 out on the economy when I first got to Seoul .

Our $10 carton of cigarettes was worth about $30 or $19 bucks in Korean money.

Any one of us could give you the current rate without thinking about it, and one of our poker games was the damndest amalgam of currencies you've ever seen: hwan, yen, MPC , U.S. coins, all mixed into one pile, all of us understanding what the various bills meant in “real” money.

The situation had some very distinct advantages to us. For instance, if you wanted to call home from the downtown Service Club, you could pay in MPC or hwan. If you sent your houseboy out on the economy to trade MPC for hwan, and then paid in that, effectively your phone call was half price. Any government-licensed or militarily-based business HAD to observe the official rate of exchange.

Effectively, we didn't. The prohibition against money trading on the economy was so often breached by so many people that, for all practical purposes, it was unenforceable, kind of like making bathtub gin in Chicago in the 1920s. That was illegal, too.

I bought my plane ticket from Seattle to Little Rock before I left Seoul . I paid for it in hwan. Half price transportation.

At almost 4-for-1, even the Koreans didn't want hwan, and many of them converted their family savings to MPC as fast as they could get a few hwan together, driving the value of the hwan down even farther.

All of this changed in one morning.

We awoke in our little compound on the outskirts of Seoul to find the front gates closed AND two armed U.S. Army MPs standing guard, with orders to let no one in or out. Although we didn't know it at the time, this was a scene being repeated at every single U.S. military post in South Korea .

The mystery as to “Why?” was answered at 9 a.m. when we were told to line up in alphabetical order at the Orderly Room/offices … and to bring all our money.

??

When we went, one at a time, into the Major's office, we were told to count out all the MPC we had on us, after which the Major gave us a receipt for it and kept the money. Later, under armed guard, he was driven off the property. When he returned a couple of hours later, we repeated the exercise only, this time, we gave him our receipts and he gave us back our money -- except it wasn't the same money. It added up the same, but the bills were a totally different color from those to which we were accustomed.

The military had had Treasury prepare and print a totally new and unique version of MPC.

When the last man got his new money, the guard came off the gate and life, for us, went back to normal. This was NOT the case out on the economy, though; there, economic life was total chaos. There were stories of people lining up outside the fences of various installations begging to buy anything of value for obscene amounts of “old” MPC. The life savings of thousands of families suddenly became just so much colorful scrap paper. Businesses were wiped out.

The only time I ever heard of this kind of evolution before had been in 1948, during the Russians' attempts to drive the U.S. , France , and Great Britain out of Berlin . The Russians figured that the key was to control the currency used in the occupied city. The Allies countered by releasing deutschmarks with a little “B” printed on them, and paying their Berlin debts with that. The same kind of utter and total secrecy, combined with swift action, did the trick, and caught the borscht-brigade with their skivvies around their ankles.

Ditto the Koreans. We never got a rumble of this move coming, and our little bunch of mass psychology bandits usually caught wind of most events as much as a month in advance of them actually happening. It was an interesting side-benefit of the job. This time, though, we didn't get a tickle until it actually happened.

The poor Koreans … they were so confused and devastated that night that one of my colleagues Cooper actually made a purchase with Monopoly ™ money that evening up in the village. The shopkeeper accepted his story that this was the new MPC.

He made a point of never going back to that store ever again after that night.

Did all this secrecy and confusion do what it was designed to do? No, not really. The unofficial exchange rate dropped briefly to 1100 hwan to the dollar, then started edging back up and was pretty much back to what it'd been when I got there by the time I left to come back to what we referred to as “The Land of the Big PX.”

No, really about the only thing that was accomplished was the bankruptcy of thousands of Korean families, and the reaping of quite a few million dollars by the U.S. government, which no longer had to worry about honoring the stranded MPC.

If there's a lesson to be learned here it's that artificial manipulation of a currency system never solves a thing. Currency – which is really nothing but a belief system, when you get right down to the bottom of it – is constantly striving to reflect reality, and you can screw with it all you want to, but all you'll ever accomplish are short-term, quite transitory gains. Every time a government decides that it needs more money, and gets it by the simple expedient of just printing more, they have really done nothing but cheapened every buck that was already out there when the government went on its printing spree.

Something to think about when our own government cuts income (i.e., taxes) on the one hand, and wants more money to buy votes with (i.e., public works, highways, new weapons systems) on the other.

Source: